Show the code

knitr::opts_chunk$set(warning = FALSE, message = FALSE)

library(tidyverse)

library(gridExtra)

library(parallel)

theme_set(theme_bw())Lecture Notes

Only functions from R-base and stats (preloaded) are required plus packages from the tidyverse for data representation and manipulation.

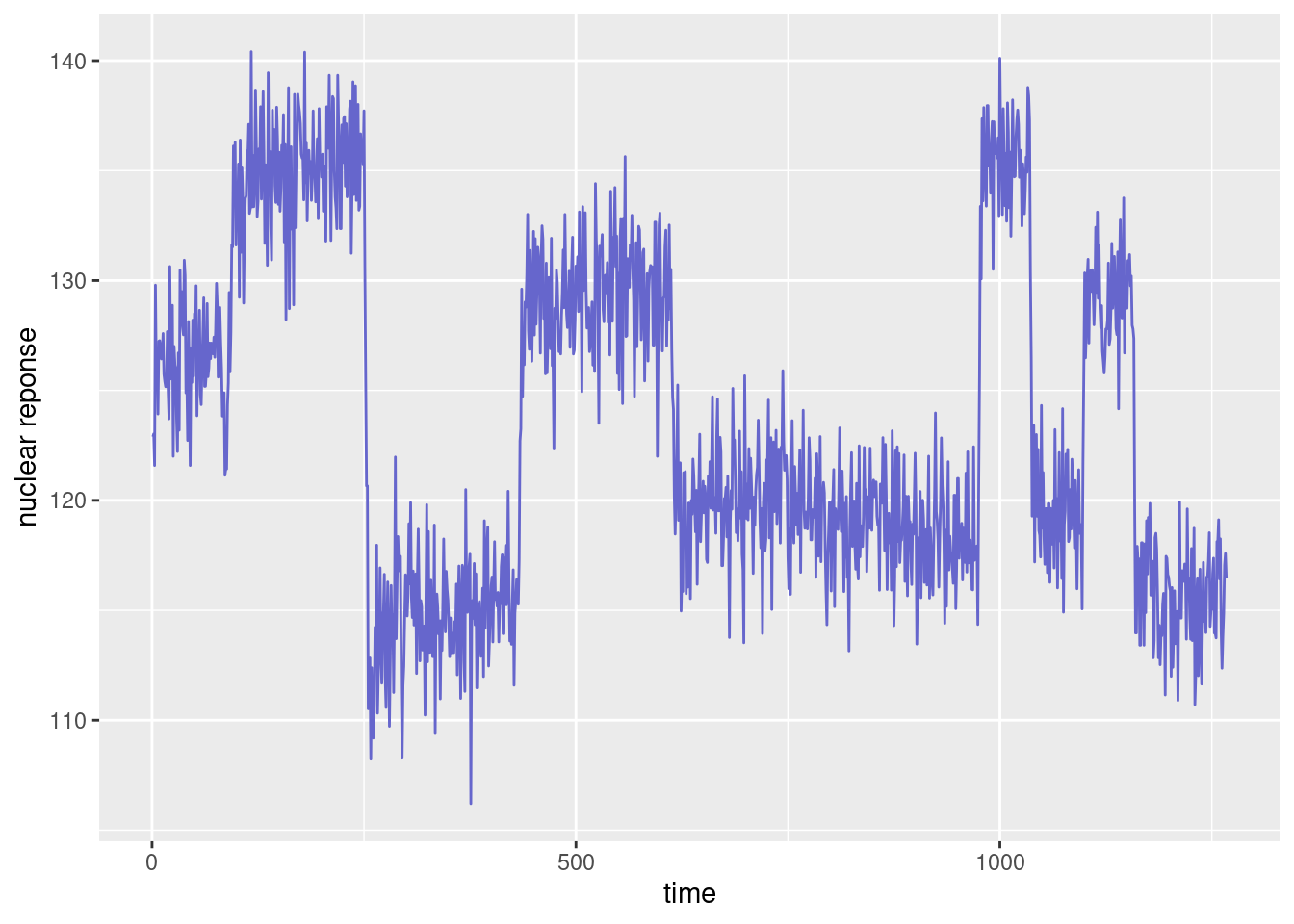

An example of well-log data is shown in Fig. 1, and consists of measurements of the nuclear magnetic response of underground rocks.

The x-axis represent either the time t at which the measurements were made, or the depth z=z(t) at which they were collected.

In drilling for oil, the problem of recovering the underlying signal of well-log data, such as that shown in the Figure above, is of practical importance.

Here, we will make the asumption that the underlying signal is piecewise constant, each constant segment relating to a stratum of a single type of rock. The jump discontinuities in the signal occur each time that a new rock stratum is met.

Hence, the problem consists in identifying

In order to solve this problem, the observed phenomena and the geological model described above now need to be, respectively, represented and translated into a mathematical model.

Our model assumes that the data fluctuates around some underlying signal f associated to the magnetic properties of the earth. Here, f(t) represents the ``true’’ nuclear reponse at time t (or at depth z(t)). Then, if t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n are the n sampling time, we can decompose y_j as

y_j = f(t_j) + \varepsilon_j \quad ; \quad 1\leq j \leq n

where (\varepsilon_j) is a sequence of residual errors. These differences between predicted and observed values include measurement errors and modeling errors, due to the natural imperfections in mathematical models for representing complex physical phenomena.

Assuming that the magnetic properties of the rock do not change within each stratum means that f is piecewise constant. More precisely, we assume that there exist discontinuity instants \tau_1, \tau_2, \ldots \tau_{K-1} and nuclear response values \mu_1, \mu_2, \ldots,\mu_K such that

f(t) = \mu_k \quad \text{if } \ \tau_{k-1} < t \leq \tau_k where K is the number of strata, and where \tau_0=0 and \tau_K=n.

Thus, for any \tau_{k-1} < j \leq \tau_k,

y_j = \mu_k + \varepsilon_j

In a probabilistic framework, the sequence of residual errors (\varepsilon_j,1 \leq i \leq n) is a sequence of random variables with mean zero. Then, (y_j) is a sequence of random variables with piecewise constant mean:

\mathbb{E}(y_j) = \mu_k \quad {\rm if} \ \tau_{k-1} < j \leq \tau_k.

Within this framework, the problem of detecting discontinuities therefore reduces to the detection of abrupt changes in the mean of (y_j).

If we are thinking in some likelihood based approach for solving this problem, we need to go a little bit further in the definition of the probability distribution of the observed data. Let us asume, for instance, that (\varepsilon_j,1 \leq j \leq n) is a sequence of independent and identically distributed Gaussian variables:

\varepsilon_j \sim^{\text{iid}} {\cal N}(0,\sigma^2).

Then, (y_j) is also a sequence of independent Gaussian variables:

y_j \sim {\cal N}(\mu_k,\sigma^2) \quad {\rm if} \ \tau_{k-1} < j \leq \tau_k

We can now express our original problem in mathematical terms. Indeed, we aim to estimate

The model is parametric model which depends on a vector of parameters \theta = (\mu_1,\ldots, \mu_K,\sigma^2,\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}).

We can then derive the likelihood function:

\begin{aligned} \ell(\theta;y_1,y_2,\ldots,y_n) &= \mathbb{P}(y_1,y_2,\ldots,y_n;\theta) \\ &= \prod_{k=1}^K \mathbb{P}(y_{\tau_{k-1}+1},\ldots ,y_{\tau_{k}};\mu_k,\sigma^2) \\ &= \prod_{k=1}^K (2\pi \sigma^2)^{\frac{-(\tau_k-\tau_{k-1})}{2}} {\rm exp}\left\{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\mu_k)^2\right\} \\ &= (2\pi \sigma^2)^{\frac{-n}{2}} {\rm exp}\left\{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\sum_{k=1}^K\sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\mu_k)^2.\right\} \end{aligned}

We can classically decompose the maximum likelihood estimation of \theta into two steps:

The second step is straightforward. We will focus here on the first step, i.e. the minimization of J(\mu_1,\ldots, \mu_K,\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}).

We can first remark that, for a given sequence of change points \tau_1, \ldots, \tau_{K-1}, J can easily be minimized with respect to \mu_1,\ldots, \mu_K. Indeed,

\begin{aligned} \hat{\mu}_k(\tau_{k-1},\tau_k) &= \overline{y}_{\tau_{k-1}+1:\tau_k} \\ &= \frac{1}{\tau_k-\tau_{k-1}}\sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} y_j \end{aligned}

minimizes \sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\mu_k)^2.

Plugging the estimated mean values (\hat{\mu}_k(\tau_{k-1},\tau_k)) into J leads to a new function U to minimize and which is now a function of \tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}:

\begin{aligned} U(\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}) &= J(\hat{\mu}_1(\tau_0,\tau_1),\ldots, \hat{\mu}_K(\tau_{K-1},\tau_{K}),\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}) \\ &= \sum_{k=1}^K\sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\overline{y}_{\tau_{k-1}+1:\tau_k})^2 \end{aligned}

Because of the normality assumption, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator of the change points coincides with the least-square (LS) estimator.

Before tackling the problem of detecting multiple change points in a time series, let us start with an easier one: the detection of a single change point.

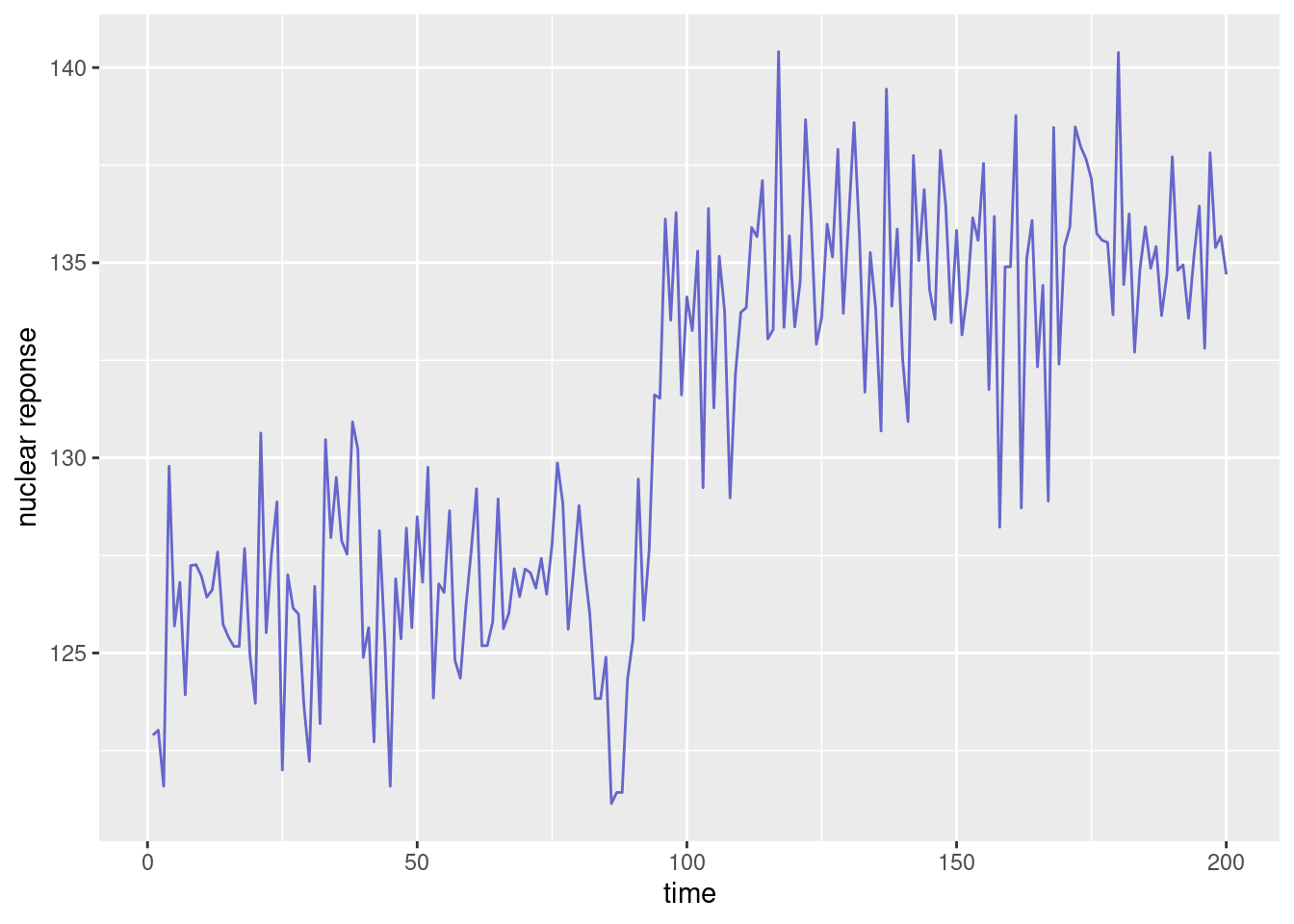

Consider, for instance, our data until time 200:

We clearly ``see’’ a jump in the mean before time 100. How can we automatically identify the time of such change?

Our model assumes that the data fluctuates around a signal which is piecewise constant: f(t) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \mu_1 & \text{if } t\leq \tau \\ \mu_2 & \text{if } t> \tau \end{array} \right.

For estimating the parameters of the model, i.e \mu_1, \mu_2 and \tau, the least-square method minimizes the residual sum of squares (RSS)

U(\tau) = \sum_{j=1}^\tau (y_j - \overline{y}_{1:\tau})^2 + \sum_{j=\tau+1}^n (y_j - \overline{y}_{\tau+1:n})^2

Then, \begin{aligned} \hat{\tau} &= {\rm arg}\min_{1\leq \tau \leq n-1} U(\tau) \\ \hat{\mu}_1 &= \overline{y}_{1:\hat\tau} \\ \hat{\mu}_2 &= \overline{y}_{\hat\tau+1:n} \\ \hat{\sigma}^2 &= \frac{U(\hat\tau)}{n} \end{aligned}

Of course, the goal is to minimize U with respect to \tau. But looking at the sequence of residuals is also valuable for diagnostic purpose. Indeed, remember that the sequence of residuals (e_j) is supposed to randomly fluctuate around 0, without showing any kind of trend. Then, a fitted model which produces residuals that exhibit some clear trend should be rejected.

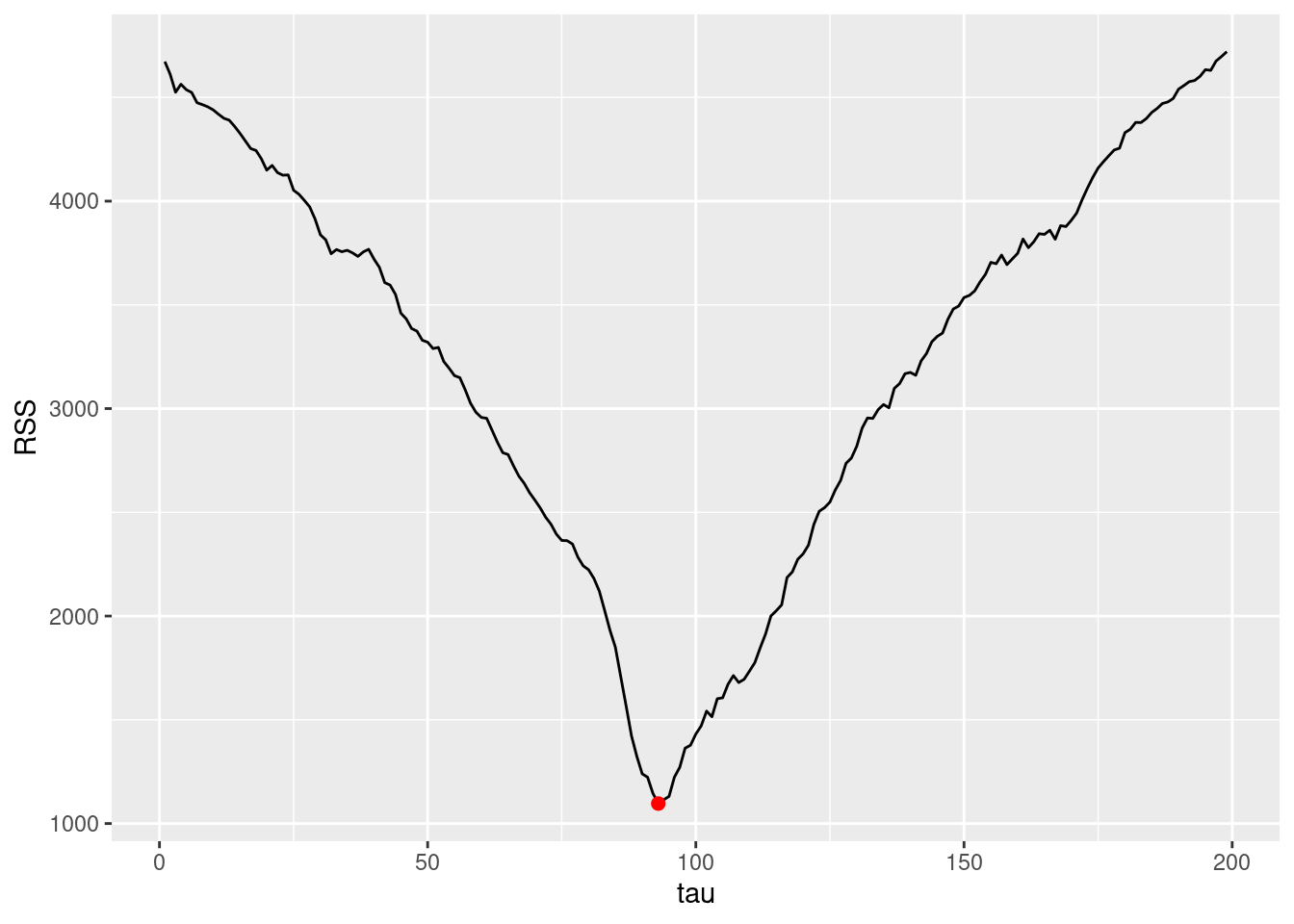

The residual sum of squares U displayed below is minimum for \hat{\tau} = 93

y <- d1$y

U <- data.frame(tau=(1:(n-1)),RSS=0)

for (tau in (1:(n-1))) {

mu1 <- mean(y[1:tau])

mu2 <- mean(y[(tau+1):n])

mu <- c(rep(mu1,tau), rep(mu2, (n-tau)))

U[tau,2] <- sum((y - mu)^2)

}

tau_hat <- which.min(U$RSS)

U_min <- U[tau_hat,2]

print(c(tau_hat, U_min))[1] 93.000 1096.269

The objective function to minimize is not convex. Then, any efficient method for convex optimization (for scalar function) may lead to some local minimum instead of the global one.

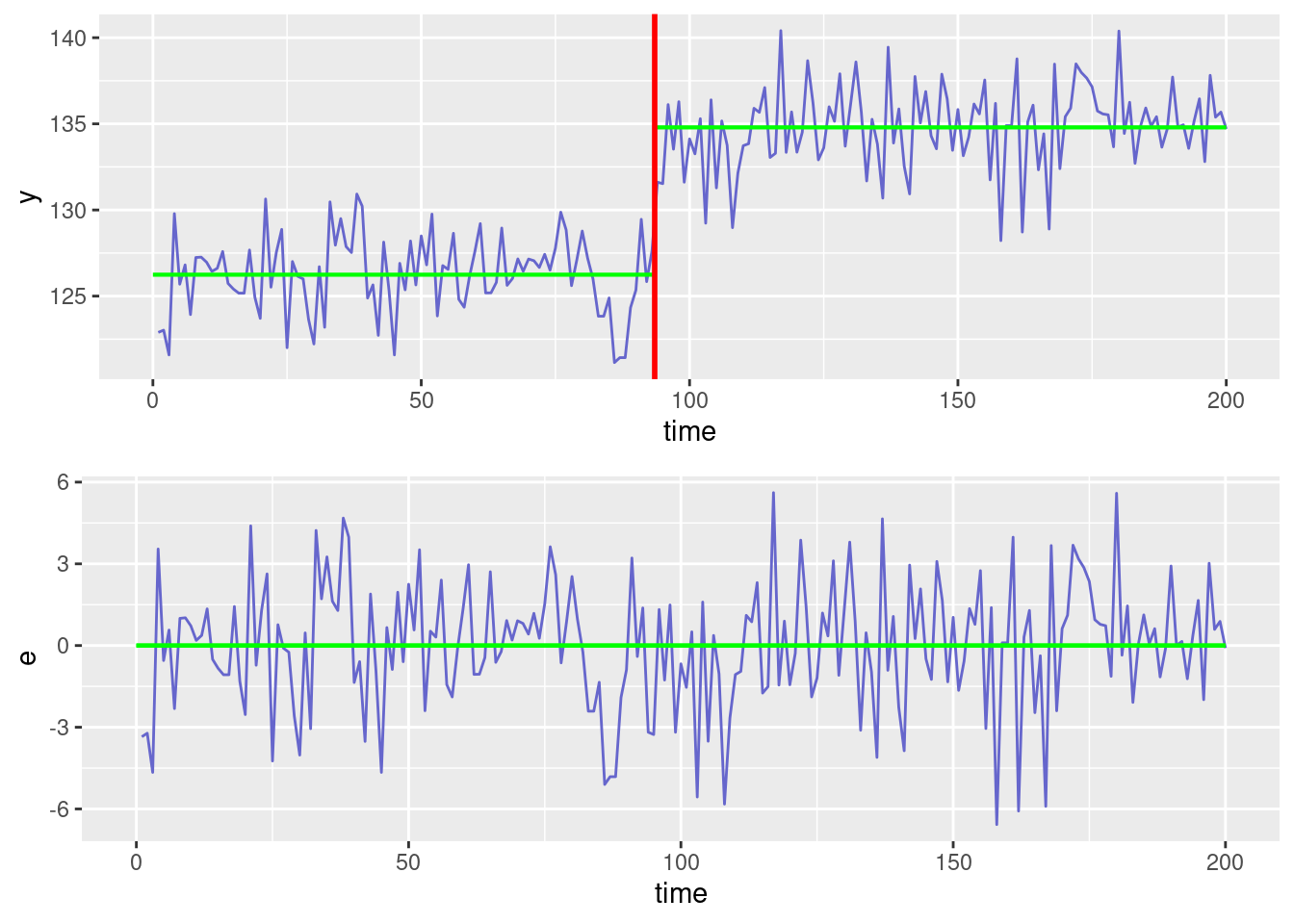

The optimal segmentation and the residuals obtained with \hat{\tau} = 93 are displayed in the next Figure.

mu1 <- mean(y[1:tau_hat])

mu2 <- mean(y[(tau_hat+1):n])

mu <- c(rep(mu1,tau_hat),rep(mu2,(n-tau_hat)))

d1$e <- y - mu

dm <- data.frame(

x1 = c(0,tau_hat+0.5),

x2 = c(tau_hat+0.5,n),

y1 = c(mu1,mu2),

y2 = c(mu1,mu2)

)

pl1 <- ggplot(data=d1) + geom_line(aes(time, y), color="#6666CC") +

geom_segment(aes(x=x1, y=y1, xend=x2, yend=y2), colour="green", data=dm, linewidth=0.75) +

geom_vline(xintercept = (tau_hat+0.5), color="red", linewidth=1)

pl2 <- ggplot(data=d1) + geom_line(aes(time, e), color="#6666CC") +

geom_segment(aes(x=0,xend=n,y=0,yend=0), colour="green", data=dm, linewidth=0.75)

grid.arrange(pl1, pl2)Warning in geom_segment(aes(x = 0, xend = n, y = 0, yend = 0), colour = "green", : All aesthetics have length 1, but the data has 2 rows.

ℹ Did you mean to use `annotate()`?

The model we are challenging with our data assumes constant mean values before and after \tau=93. Residuals do not exhibit any clear trend. Thus, based on this diagnostic plot, there is no good reason for rejecting this model.

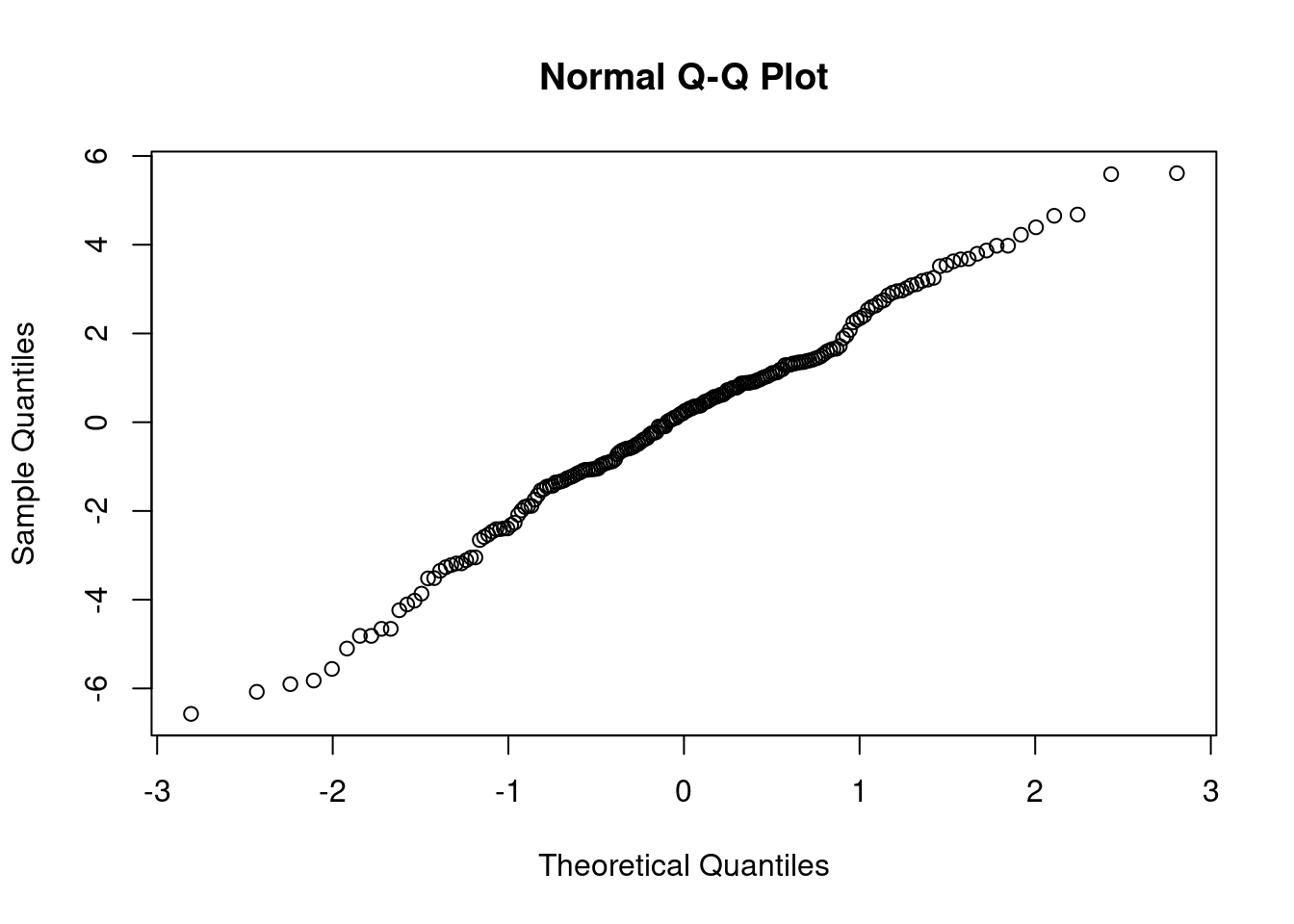

The assumptions made for the probability ditribution of the residual errors could also be tested:

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: d1$e

W = 0.98776, p-value = 0.08299These results mean that assuming that the residuals are i.i.d. is acceptable. Then, we can be quite confident that the Least-Square criterion used for estimating the change-points has very good (not to say optimal) statistical properties.

Until now, the main conclusion of this study is that a model with constant mean values before and after \tau=93 cannot be rejected.

Nevertheless, we would come to the same conclusion with \tau=92 or \tau=94 but probably not with \tau=90 or \tau=110.

Indeed, even if \hat{\tau}=93 is the ML estimate of \tau, there remains some degree of uncertainty about the location of the change point since \hat{\tau} is a random variable.

What can we say about the ML estimator \hat{\tau} and the estimation error \hat{\tau} - \tau^\star, where \tau^\star is the “true” change point?

The theoretical properties of \hat{\tau} are not easy to derive (this is beyond the scope of this course). On the other hand, Monte Carlo simulation enables us to easily investigate these properties.

Then, the change-point is estimated for each of these simulated series and the sequence of estimates (\hat\tau_1, \hat\tau_2, \ldots , \hat\tau_M) is used:

For a given n, the properties of \hat{\tau} only depends on (\mu_2-\mu_1)/\sigma. We therefore arbitrarely fix \mu_1=0 and \sigma^2=1.

As with any Monte Carlo study, increasing the Monte Carlo size M improve the accuracy of the results, i.e. the empirical distribution of (\hat\tau_m, 1 \leq m \leq M) looks more and more like the unknown probability distribution of \hat\tau, but the computational effort is also increased.

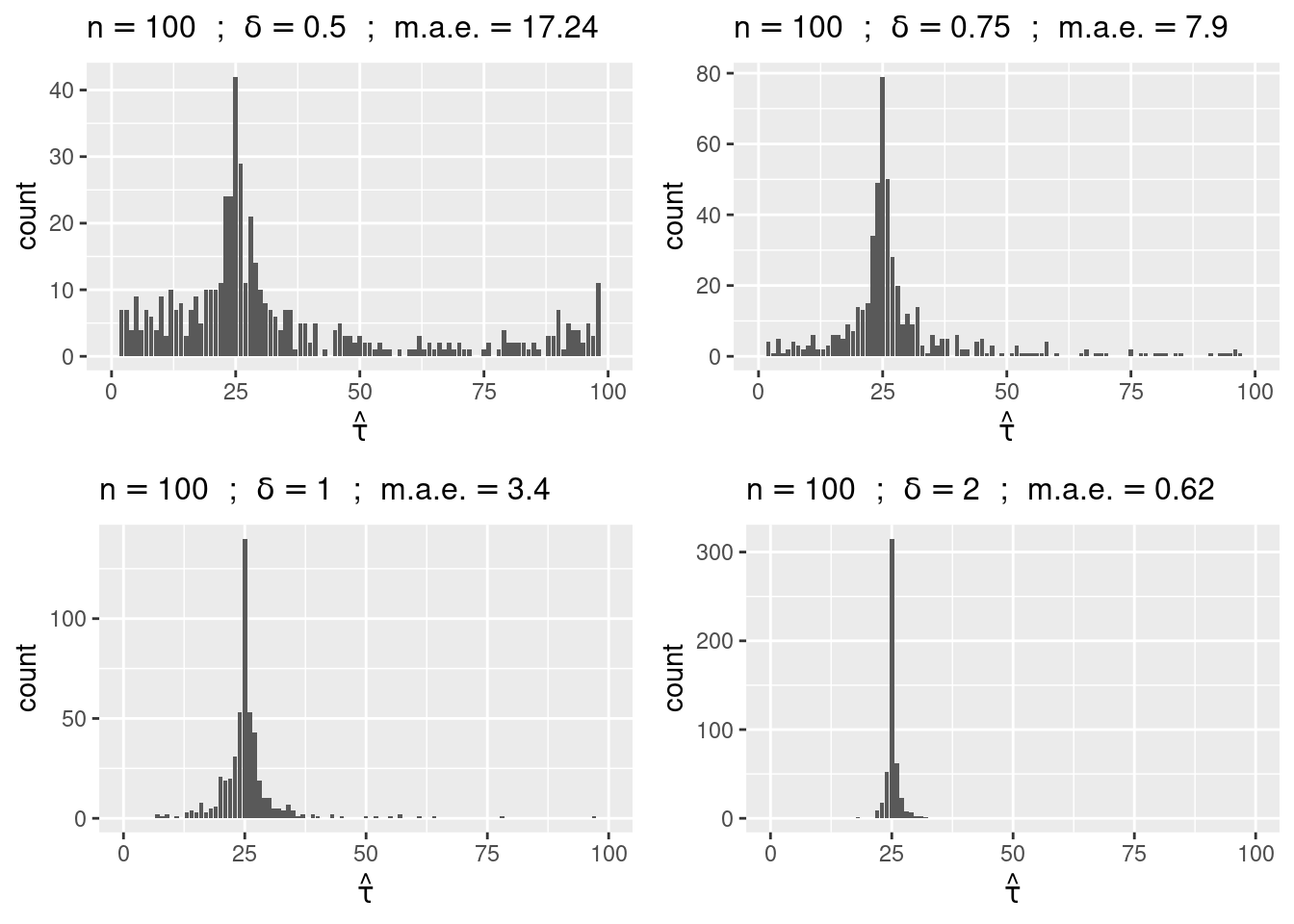

Note that, for a given number n of data points and a given change point \tau^\star, the estimation error decreases with the absolute difference of the two means \delta = |\mu_2-\mu_1|.

Let us display the ditribution of \hat{\tau} estimated by Monde Carlo simulation with n=100 and \delta=0.5, 0.75, 1, 2.

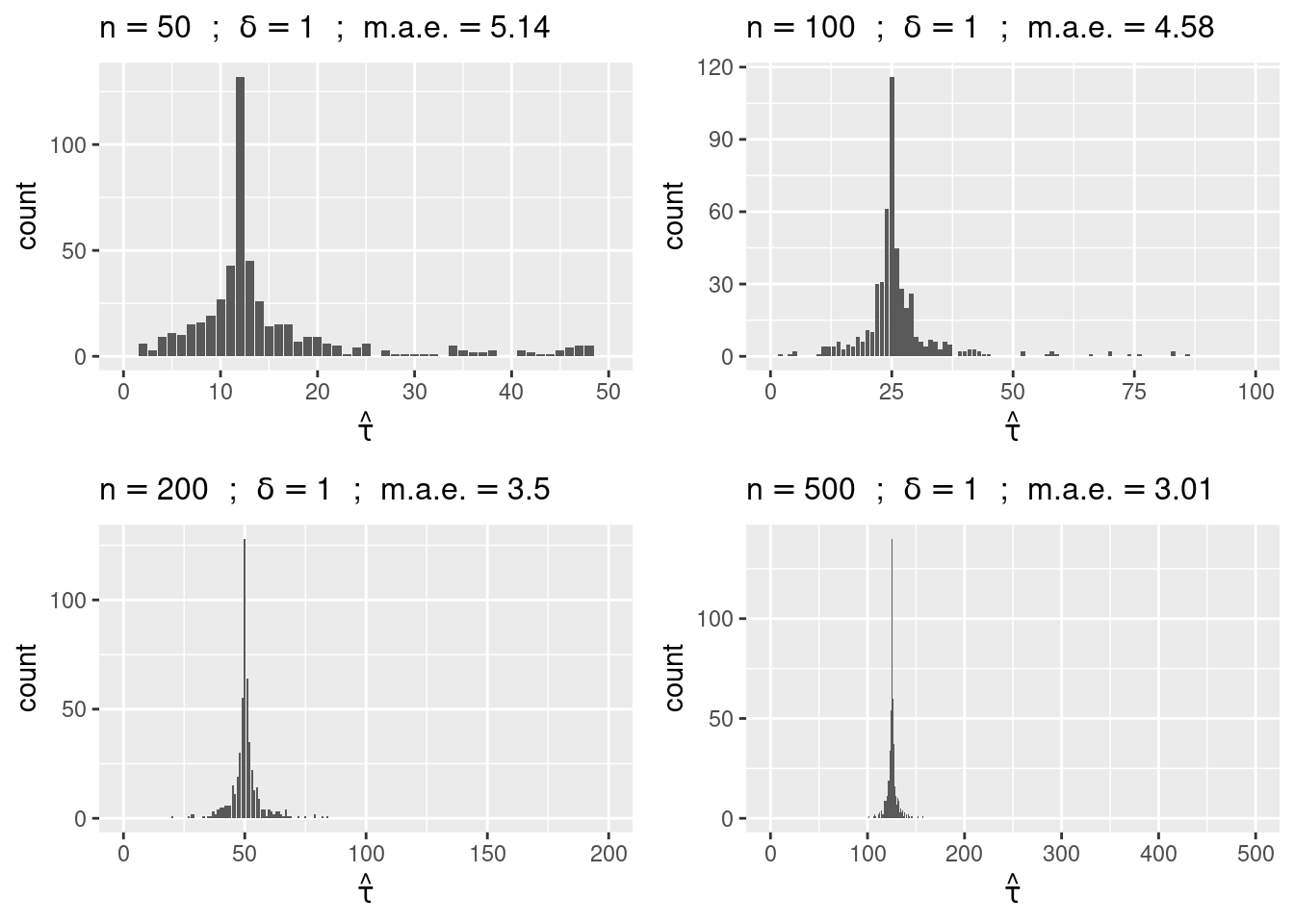

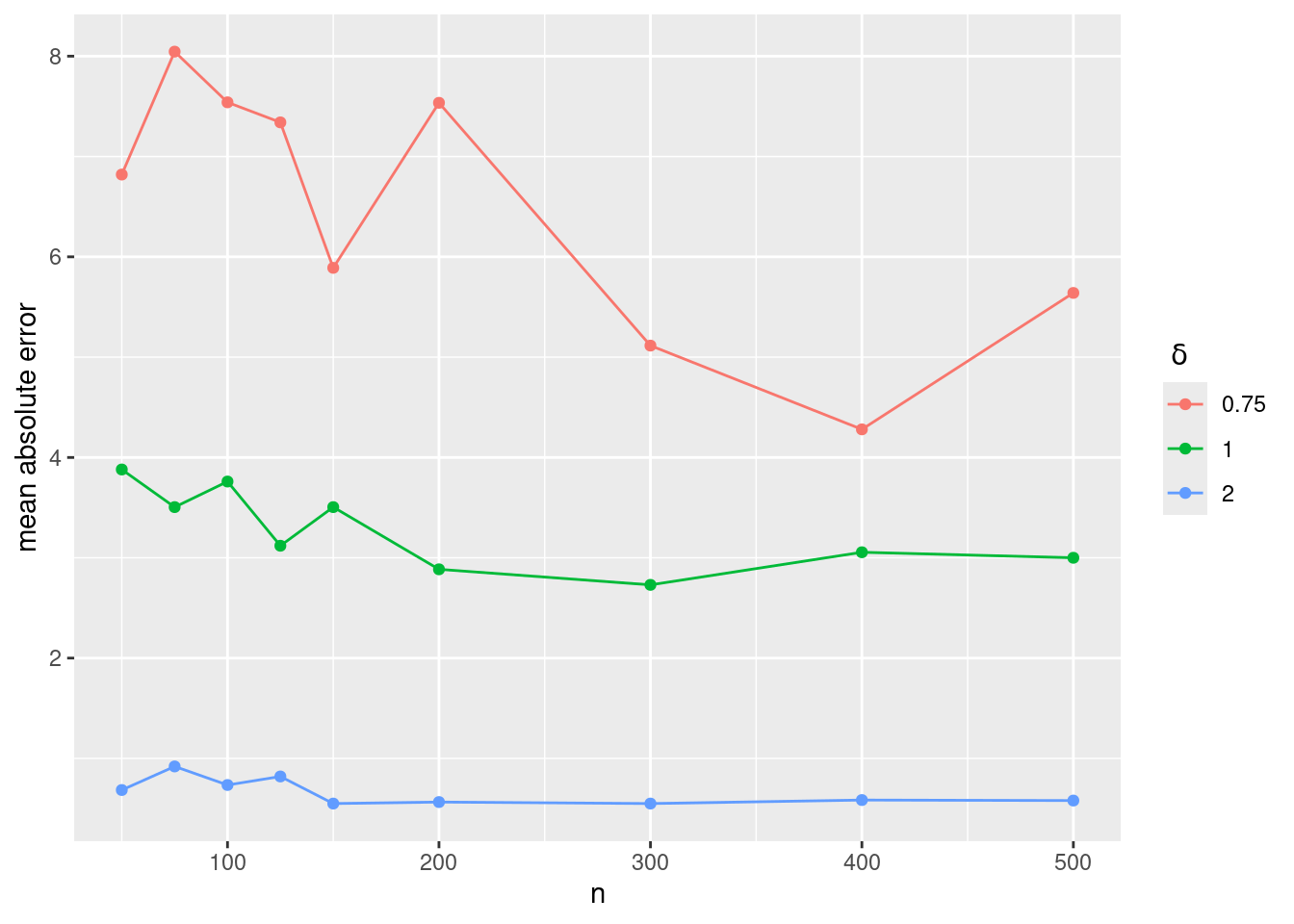

Let us display the mean absolute error obtained with different value of n and \delta:

M <- 200

vd <- c(0.75, 1, 2)

vn <- c(50,75,100,125,150, seq(200,500,by=100))

E <- NULL

for (j in (1:length(vd)))

{

delta <- vd[j]

Ej <- data.frame(delta=delta, n=vn, mae=NA)

for (k in (1:length(vn))) {

n <- vn[k]

e <- cpf(tau.star=n/2, delta, n, M, plot=FALSE)

Ej$mae[k] <- mean(abs(e))

}

E <- rbind(E, Ej)

}

ggplot(data=E, aes(n,mae, colour=factor(delta))) + geom_line() + geom_point() + ylab("mean absolute error") + scale_colour_discrete(name=expression(paste(" ",delta)))

This plot shows that the expected absolute error \mathbb{E}{|\hat\tau-\tau^\star|} does not depends on n but decreases with \delta.

The main theoretical result concerning \hat{\tau} for our Gaussian model (assuming i.i.d. residual) states that |\hat{\tau} - \tau^\star| = {\cal O}_{\rm P}(\frac{1}{\delta^2}), which means that \mathbb{P}(\delta^2|\hat{\tau} - \tau^\star| > A) tends to 0 as A goes to infinity. In other words, when \delta increases, the expected absolute error decreases, in theory, as 1/\delta^2.

We can easily check by simulation that the empirical absolute error (displayed above) multiplied by \delta^2 is a random variable which does not exhibit any dependence with respect to n and \delta.

Until now, we only considered the problem of estimating a change point, assuming that there exits a change in the mean of the series (y_j,1\leq j \leq n). But what happens if there is no jump in the underlying signal?

We therefore need some criteria to decide if the change that has been detected is statistically significant or not. We can formulate our problem in terms of two hypotheses:

Before considering the general problem of testing {\cal H}_0 against {\cal H}_1, consider, for any 1\leq \tau \leq n-1, the simple alternative hypothesis

Under {\cal H}_\tau, the model is

The problem of testing if the mean changes at a given time \tau thus reduces to testing if the means \mu_1 and \mu_2 (before and after \tau) are equal.

Let us test, for instance, if the means before and after t=50 are equal:

Two Sample t-test

data: y[1:tau] and y[(tau + 1):n]

t = -9.1881, df = 198, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-7.462614 -4.825304

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

126.2105 132.3544 The test is clearly significant: we can conclude that the means before and after t=50 are different. Nevertheless, this result does not allows us to conclude that the mean jumps at time t=50. Indeed, we would also reject the null hypothesis for other possible values of \tau, including 150 for instance:

Two Sample t-test

data: y[1:150] and y[(151):n]

t = -8.1992, df = 198, p-value = 2.997e-14

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-7.018332 -4.296874

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

129.4041 135.0617 Let us compute the test statistics S_\tau and the associated p-value p_\tau for all possible values of \tau:

t.stat <- t.pval <- NULL

for (tau in (1:(n-1))) {

test.tau <- t.test(y[1:tau],y[(tau+1):n],var.equal = T)

t.stat <- c(t.stat , abs(test.tau$statistic))

t.pval <- c(t.pval , test.tau$p.value)

}

tau.max <- which.max(t.stat)

S.max <- t.stat[tau.max]

p.min <- t.pval[tau.max]

print(c(tau.max, S.max, p.min)) t t

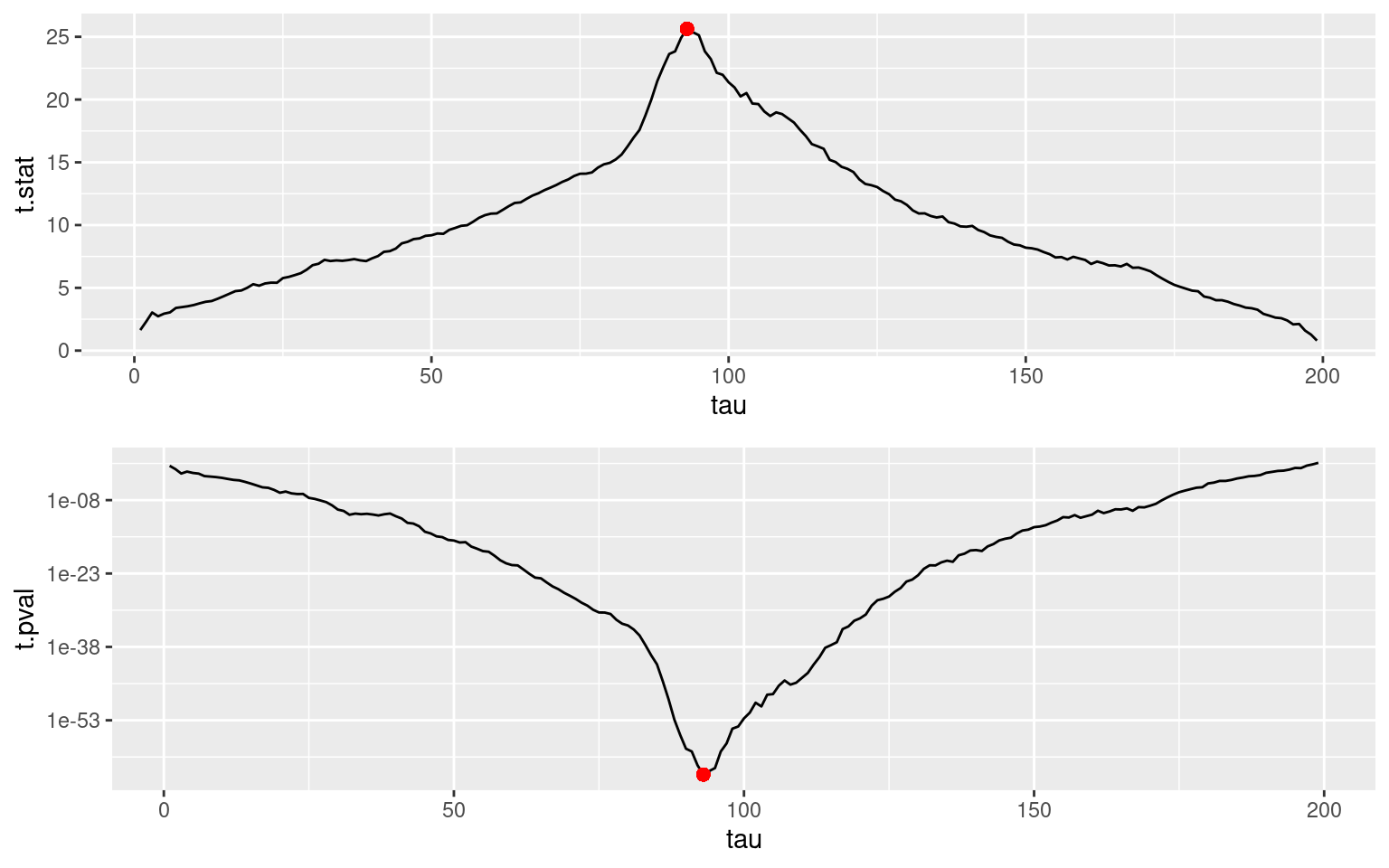

9.300000e+01 2.563787e+01 7.937425e-65 pl1 <- ggplot(data.frame(tau=1:(n-1), t.stat)) + geom_line(aes(tau,t.stat)) +

geom_point(aes(x=tau.max,y=S.max), colour="red", size=2)

pl2 <- ggplot(data.frame(tau=1:(n-1), t.pval)) + geom_line(aes(tau,t.pval)) +

geom_point(aes(x=tau.max,y=p.min), colour="red", size=2) +

scale_y_continuous(trans='log10')

grid.arrange(pl1, pl2, nrow=2)Warning in geom_point(aes(x = tau.max, y = S.max), colour = "red", size = 2): All aesthetics have length 1, but the data has 199 rows.

ℹ Did you mean to use `annotate()`?Warning in geom_point(aes(x = tau.max, y = p.min), colour = "red", size = 2): All aesthetics have length 1, but the data has 199 rows.

ℹ Did you mean to use `annotate()`?

We can remark that the sequence of t-statistics (S_\tau,1\leq \tau\leq n-1) reaches its maximum value when the sequence of p-values (p_\tau,1\leq \tau\leq n-1) reaches its minimum value, i.e. when \tau=\hat\tau=93.

Let’s go back now to our original problem of testing if there is a change at some unknown instant \tau^\star. The decision rule now depends on S_{\rm max}=\max(S_\tau,1\leq \tau\leq n-1) (or equivalently on p_{\rm min}=\min(p_\tau,1\leq \tau\leq n-1).

Indeed, we will reject {\cal H}_0 if S_{\rm max} is larger than some given threshold. More precisley, in order to control the level of the test, we will reject the null if S_{\rm max} > q_{S_{\rm max},1-\alpha}, where q_{S_{\rm max},1-\alpha} is the quantile of order 1-\alpha of S_{\rm max}, i.e. such that \mathbb{P}(S_{\rm max} > q_{S_{\rm max},1-\alpha}) = \alpha

S_{\rm max} is the maximum value of a collection of n-1 random variables having a t distribution under the null hypothesis. Furthermore, these n-1 random variables are dependent since they all are function of the same serie (y_j,1\leq j \leq n).

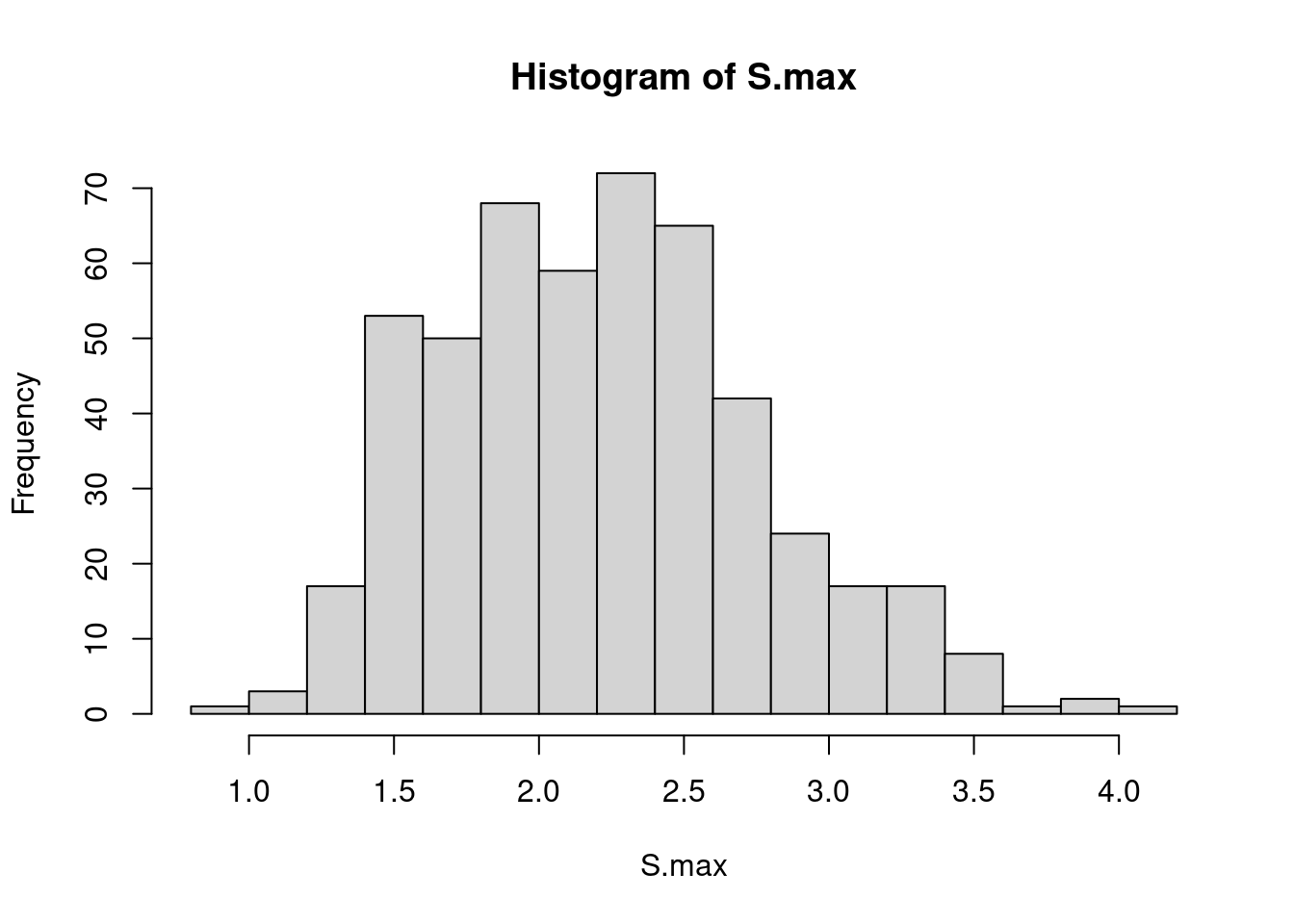

The distribution of S_{\rm max} is then quite complex… but it can be approximated by Monte Carlo simulation:

M <- 500

S.max <- NULL

for (m in (1:M)) {

y.sim <- rnorm(n)

t.stat <- NULL

for (tau in (1:(n-1))) {

test.tau <- t.test(y.sim[1:tau],y.sim[(tau+1):n],var.equal = T)

t.stat <- c(t.stat , abs(test.tau$statistic))

}

tau.max <- which.max(t.stat)

S.max <- c(S.max, t.stat[tau.max])

}

hist(S.max, breaks=20)

Quantiles of the distribution of S_{\rm max} can then be estimated by the empirical quantiles of the simulated sequence (S_{\rm max,m} , 1 \leq m \leq M):

We can use these empirical quantiles for designing the test and decide, for instance, to conclude that there is a change if S_{\rm max}> 3.21 (significance level = 0.05).

Note that these quantiles are greater that the quantiles of a t-distribution:

We have seen that the maximum likelihood method and the least-square method both consist in minimizing the function U(\tau) defined as

U(\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}) = \sum_{k=1}^K\sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\overline{y}_{\tau_{k-1}+1:\tau_k})^2

The algorithm used for estimating a single change point consists in an exhaustive search of this minimum. Such brute-force search becomes unfeasible when the number of change points increases. Indeed, the number of configurations of change points to compare is of the order of \left(\begin{array}{c}n \\ K \end{array} \right)

A dynamic programming algorithm is extremly efficient for solving this optimization problem with a time complexity O(n^2) only.

Imagine we want to do a trip from 1 to n in K steps. Let \tau_1, \tau_2, , \tau_{K-1} be a given position of travel stops. Assume now that the kth step between stop \tau_{k-1} and stop \tau_k has a cost u(\tau_{k-1},\tau_k) that only depends on (y_{\tau_{k-1}+1}, \ldots , y_{\tau_k}). Then, the total cost of this trip is

U(\tau_1,\ldots,\tau_{K-1}) = \sum_{k=1}^K u(\tau_{k-1},\tau_k) In the particular case of changes in the mean, u(\tau_{k-1},\tau_k) = \sum_{j=\tau_{k-1}+1}^{\tau_k} (y_j-\overline{y}_{\tau_{k-1}+1:\tau_k})^2 The algorithm uses a recursive optimization scheme. Indeed, if we know how to go (i.e. where to stop) from any position j to n in k-1 steps, then, for any j^\prime<j, the optimal trip from j^\prime to n in k steps and that first stops at j is already known.

Let u^{(k-1)}(j,n) be the cost of the optimal travel from j to n in k-1 steps. Then,

u^{(k)}(j^\prime,n) = \min_{j^\prime< j < n}\left(u(j^\prime,j) + u^{(k-1)}(j,n)\right) and we now know how to go from j^\prime to n in k steps.

This algorithm is implemented in the R function dynProg.mean. For a given maximum number of segments K_{\rm max}, this function returns:

dynProg.mean <- function(y, Kmax, Lmin=1) {

N_breaks <- Kmax - 1 # number of breaks

n <- length(y) # number of point

## Compute the cost u(tau_k,tau_k+1) for all tau_k, tau_{k+1}

u <- matrix(Inf, nrow = n, ncol = n)

for (tau_1 in (1:(n - Lmin + 1))) {

for (tau_2 in ((tau_1 + Lmin - 1):n)) {

yk <- y[tau_1:tau_2]

nk <- tau_2-tau_1 + 1

u[tau_1,tau_2] <- sum(yk^2) - (sum(yk)^2)/nk

}

}

U <- vector(length = Kmax) # U is the total cost

U[1] <- u[1,n] # U(1) is the cost no breaks (K = 1, a single segment)

u_j_n <- u[,n] # optimal travel for j to n in (current) number of breaks

# matrix giving the position of of the successive breaks

Pos <- matrix(nrow = n, ncol = N_breaks)

Pos[n,] <- rep(n, N_breaks) # last breaks is always n

Tau <- matrix(nrow = N_breaks, ncol = N_breaks) # matrix of change points/breaks

for (k in 1:N_breaks){

for (j in 1:(n-1)){

## dynamic programming formula

u_jprime_n <- u[j, j:(n-1)] + u_j_n[(j+1):n]

u_j_n[j] <- min(u_jprime_n)

## position of the best breaks through j

Pos[j,1] <- which.min(u_jprime_n) + j

if (k > 1) { Pos[j,2:k] <- Pos[Pos[j,1],1:(k-1)] }

}

## store results for current number of breaks

U[k + 1] <- u_j_n[1]

Tau[k, 1:k] <- Pos[1,1:k] - 1

}

sigma_hat <-

list(Segments = Tau,

RSS = data.frame(K = 1:Kmax, value = U),

BIC = data.frame(K = 1:Kmax, value = n * log(U) + log(n)*(1:Kmax) ))

}plot_segmentation <- function(data, segmentation, Kopt) {

n <- length(data$y)

Topt <- c(0,segmentation[(Kopt-1),1:(Kopt-1)],n)

Tr <- c(0,Topt[2:Kopt]+0.5,n)

dm <- data.frame()

for (k in (1:Kopt)) {

m <- mean(y[(Topt[k]+1):Topt[k+1]])

dm <- rbind(dm, c(Tr[k],Tr[k+1],m,m))

}

names(dm) <- c("x1","x2","y1","y2")

pl <- ggplot(data=data) + geom_line(aes(time, y), color="#6666CC") +

geom_vline(xintercept = Tr[2:Kopt], color="red", size=0.25) +

geom_segment(aes(x=x1, y=y1, xend=x2, yend=y2), colour="green", data=dm, size=0.75)

pl

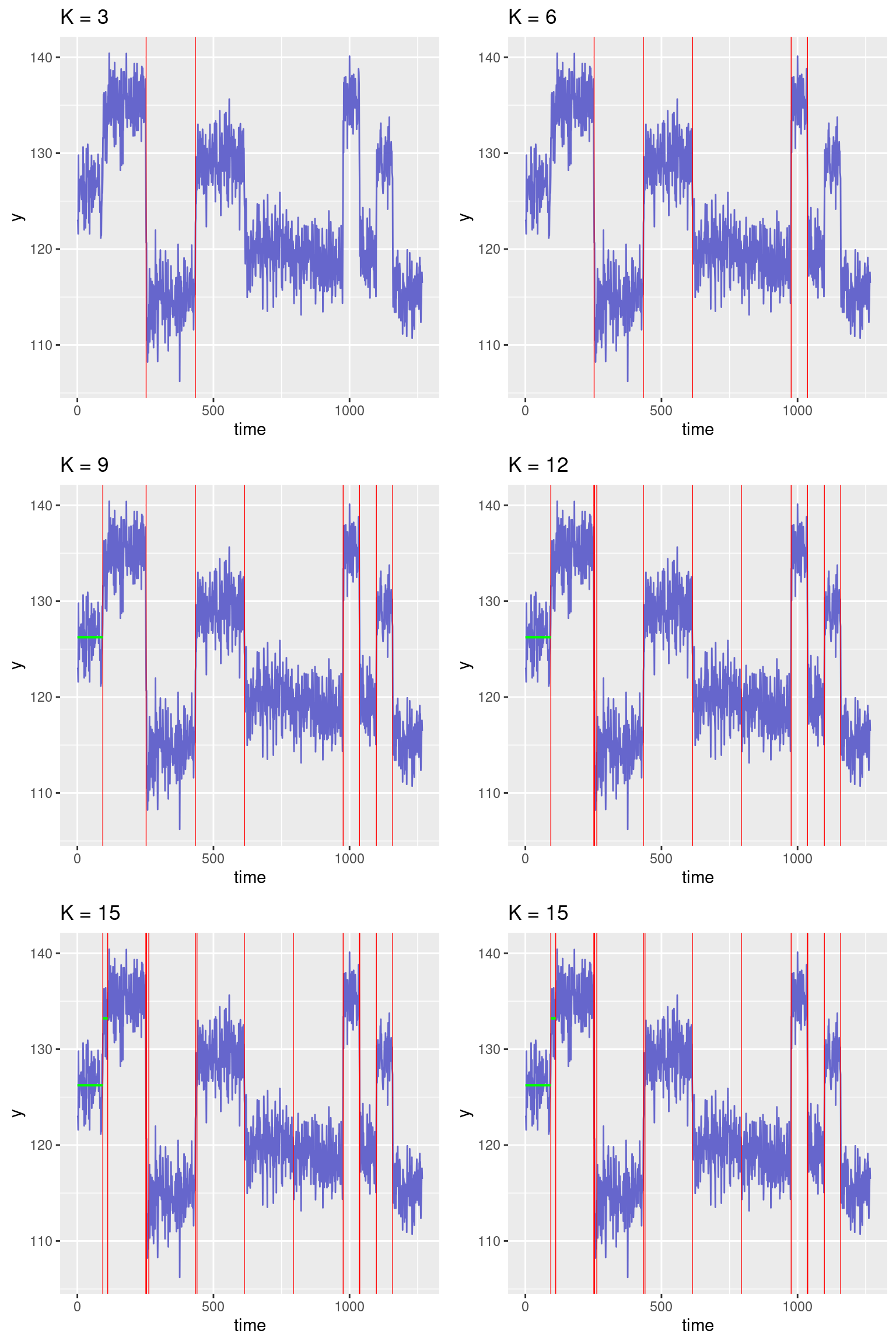

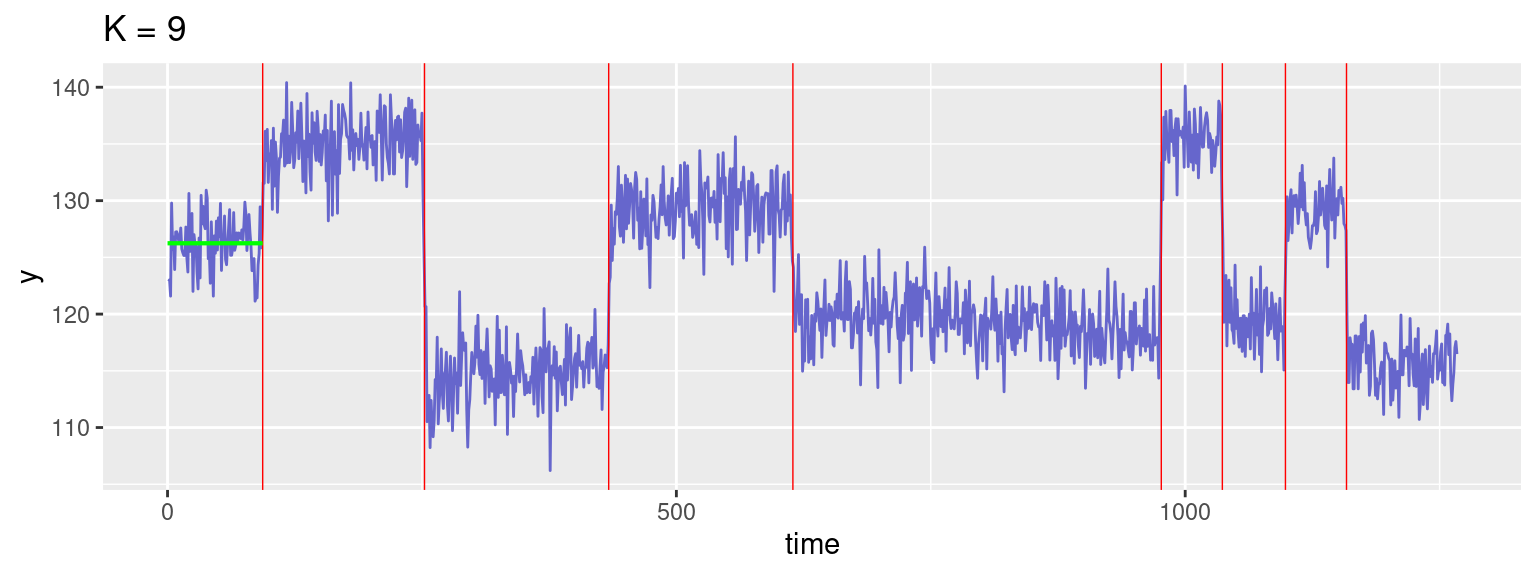

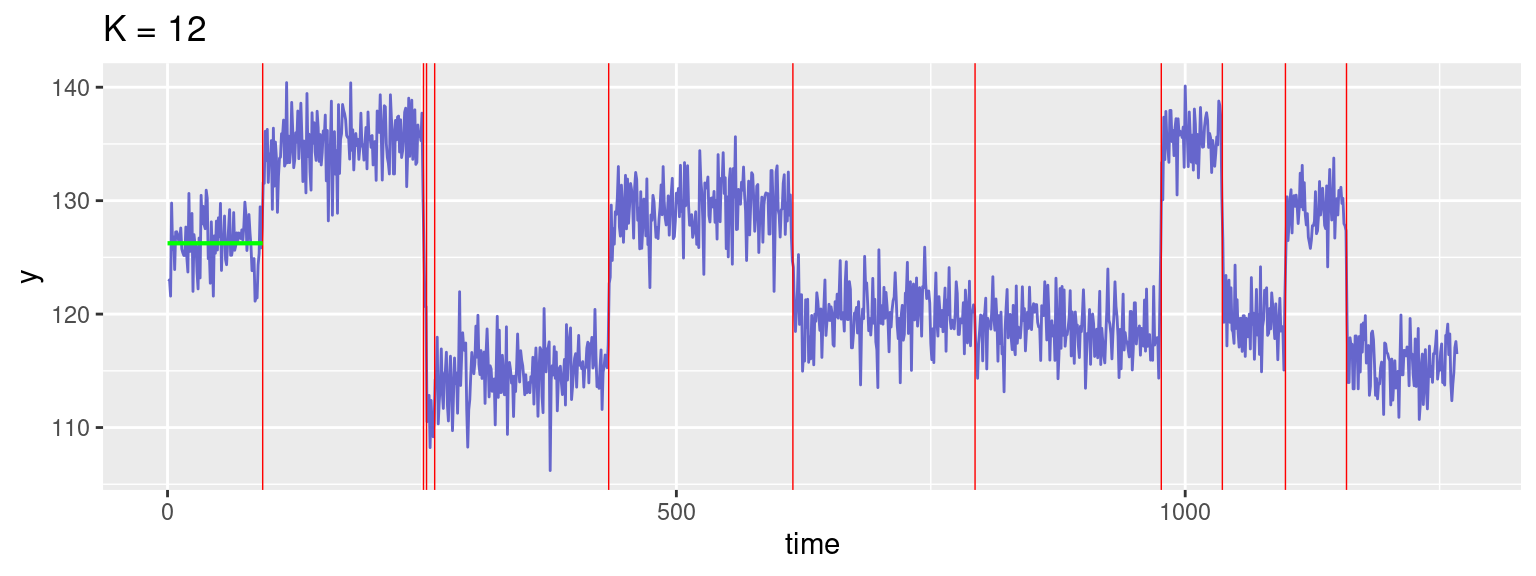

}Let us represent the segmentation obtained for K = 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20 change-points:

Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.p2 <- plot_segmentation(d, seg, 6) + ggtitle("K = 6")

p3 <- plot_segmentation(d, seg, 9) + ggtitle("K = 9")

p4 <- plot_segmentation(d, seg, 12) + ggtitle("K = 12")

p5 <- plot_segmentation(d, seg, 15) + ggtitle("K = 15")

p6 <- plot_segmentation(d, seg, 20) + ggtitle("K = 20")

grid.arrange(p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p5, ncol=2)Warning: Removed 3 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).Warning: Removed 6 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).Warning: Removed 8 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).Warning: Removed 11 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).Warning: Removed 13 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).

Removed 13 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).

We see a significant improvement of the fit when we start adding change points. The sequence of residuals also looks more and more as a sequence of i.i.d. centered random variables. Nevertheless these improvements suddenly become less obvious after detecting the main 8 jumps that are clearly visible. Indeed, adding more change points only allows to detect very small changes in the empirical mean and reduces the residual sum of squares very slightly.

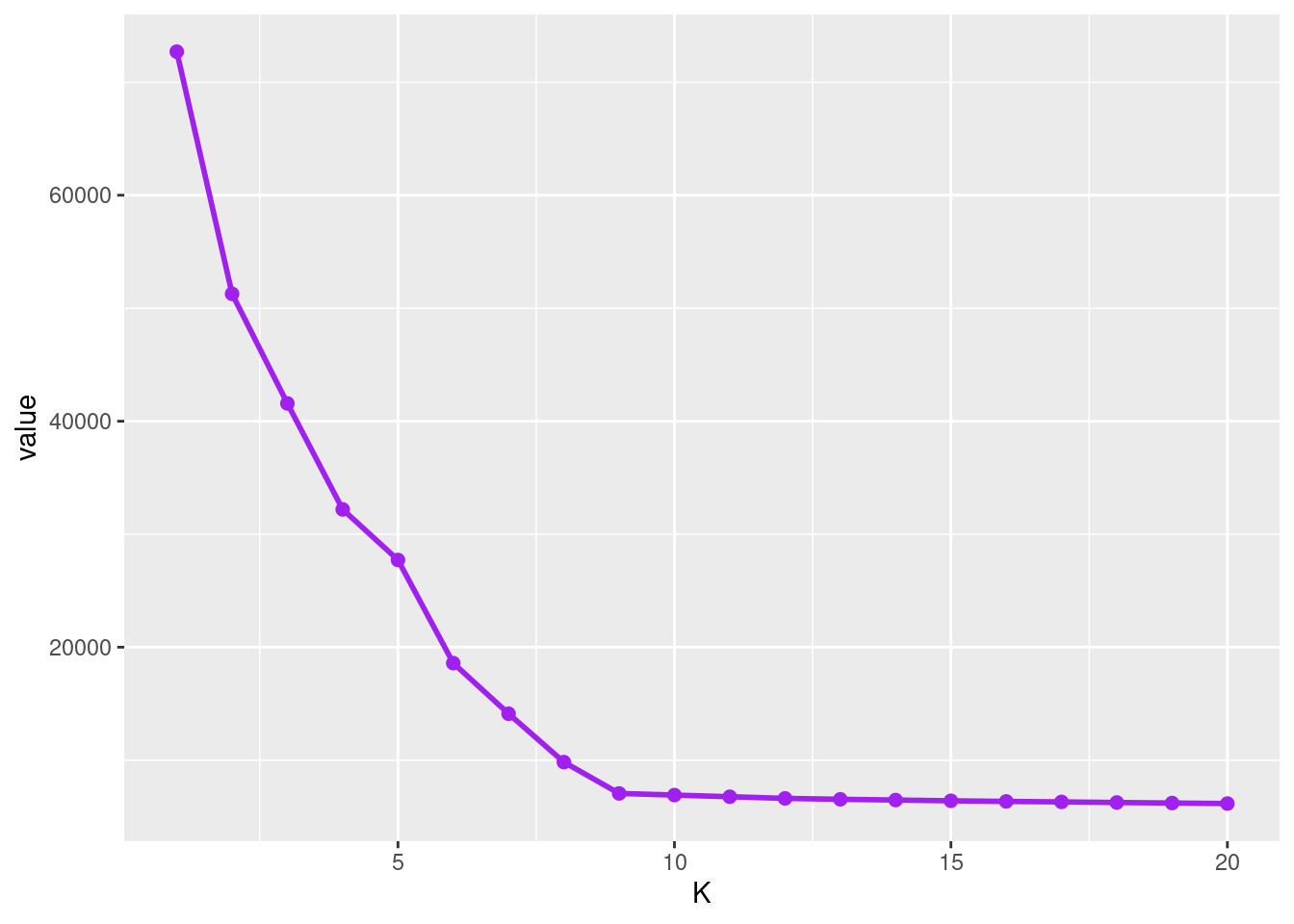

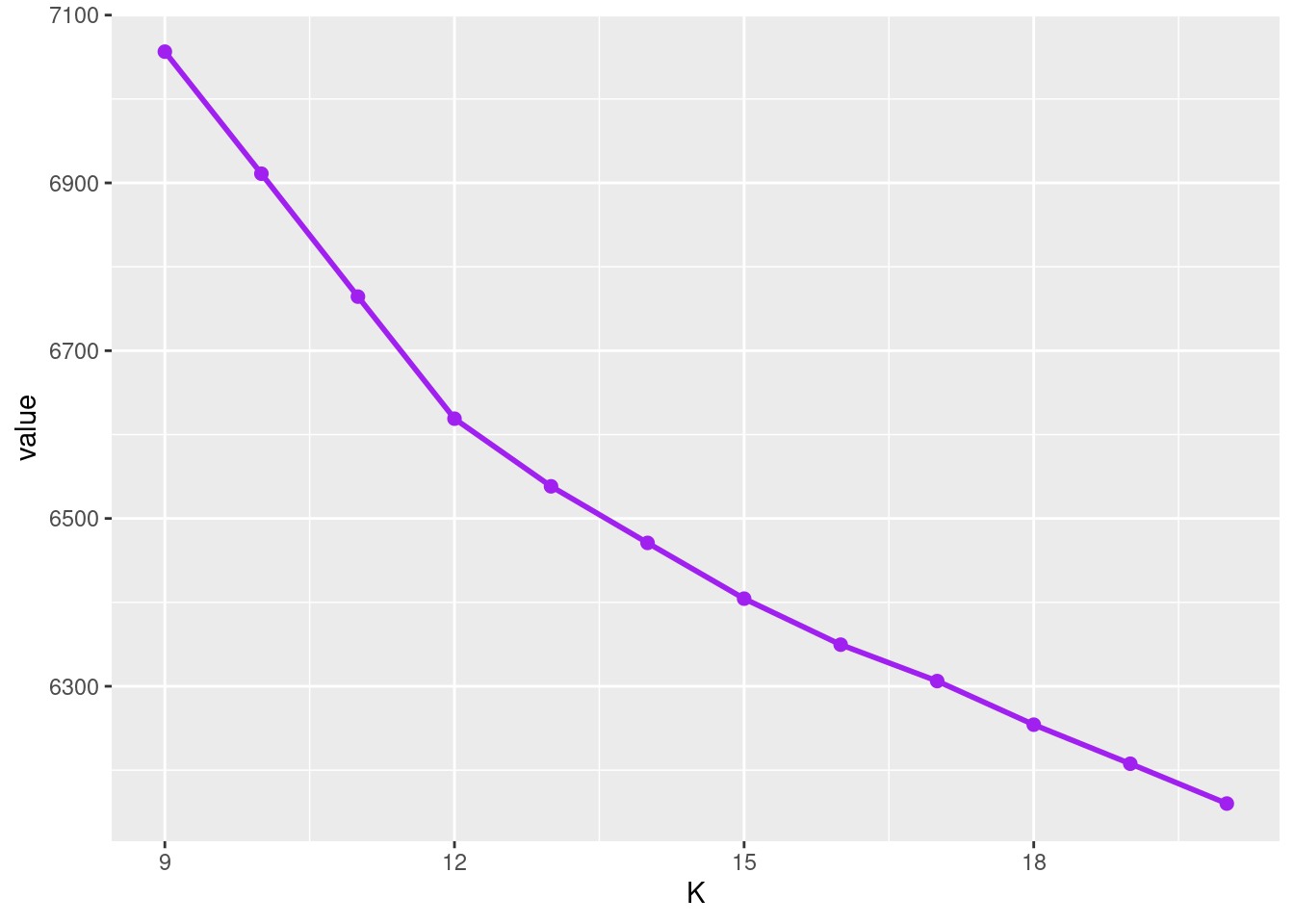

A method for selecting an “optimal” number of segments consists in looking at the objective function obtained with different number of segments.

As expected, the sequence (U_K , 1\leq K\leq K_{\rm max}) decreases significantly between K=1 and K=9. Then, the decrease is much lower. The value of K at which the slope abruptly changes provides an estimate \hat{K} of the number of segments.

We then deduce the \hat{K}-1 change points (\hat\tau_{\hat{K},1}, \ldots , \hat\tau_{\hat{K},\hat{K}-1} )

Warning: Removed 8 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).

Let’s have a look at the objective function between K=9 and K=20.

pl <- ggplot(data=res$RSS[9:20,]) + aes(x = K, y = value) +

geom_line(linewidth=1, colour="purple")+ geom_point(size=2, colour="purple")

pl

We notice another change in the slope at K=12. The segmentation with K=12 segments is displayed below.

[1] 93 251 254 262 433 614 793 976 1036 1098 1158Warning: Removed 11 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_segment()`).

Statistical modelling of the observed data allows us to get the optimal segmentation for any number of strata K and propose some possible number of strata (K=9 and K=12 appear to be the favourite numbers of strata). However, it is important to keep in mind that only a geologist or a geophysicist may decide which change points are physically significant. It is not a statistical criteria that can decide, for instance, if the change point located at t=793 (obtained with K=12 segments) should be associated to a significant change of the magnetic properties of the stratum identified between t=614 and t=976.

The interested reader may look at the following references: Fearnhead and Rigaill (2019), Fearnhead and Rigaill (2019), Picard et al. (2004), Lavielle and Moulines (2000), Bai (1994)